What Are The Best Strategies For Teaching Students To Listen Actively?

Active listening involves employing different behaviors to enhance understanding among two or more people in a conversation.

An active listener is present in the conversation. They hear the speaker’s words and pay attention to their body language in order to make connections. The brain is engaged, picking up on overarching themes or repeated phrases that indicate the essence of a speaker’s message. The fewer people engaged in a conversation, the more difficult it is to feign active listening.

Such a skill is particularly important for 21st-century learners. In an age of information overload and distractions galore, some may find it more difficult to sustain attention during a conversation. Active listening conveys empathy and understanding. It builds trust and confidence. It signals that the listener cares about the speaker and/or their message.

Active listening is, perhaps, the foundation to a successful Socratic Seminar, Fishbowl conversation, or round of Philosophical Chairs. Beyond class discussions, active listening is essential for assignments and activities that require students to read, listen to podcasts, interview subjects, provide peer feedback, and participate in restorative justice sessions.

We can set up a dichotomy between active and passive listening–it’s (mostly) obvious when someone is feigning interest, mildly distracted, or totally checked out of a conversation. Teachers and students alike can tell, when they are speaking, if someone is annoyed, preoccupied, or bored.

随着教师将更多的协作学习元素纳入他们的课程计划时,至关重要的是,他们对积极倾听学生的榜样至关重要。在高中层面上,建模主动聆听与在基础级别的教育者一样重要,而不是在这些看似简单的技能中实践他们的学生。下面,我们列出了十项策略,以为学生建模,以提高他们的主动听力技巧。学生应该有多种机会来练习这些技能,我们为教师如何建模每个策略提供了一些想法。如果有任何读者使用我们尚未列出的活动,我们很乐意听到他们的声音。

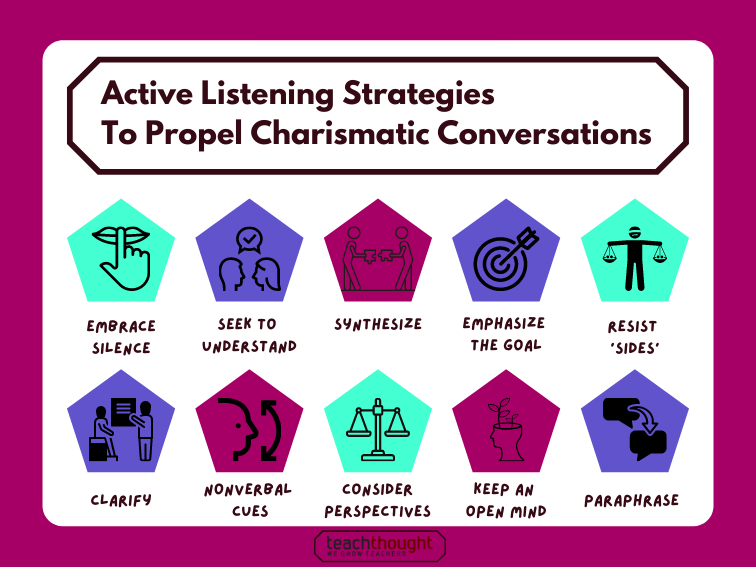

10 Active Listening Strategies To Propel Charismatic Conversations Among Students (And Teachers!)

(1)使用肯定的面部提示,肢体语言,手势和非语言标志

With active listening, the listener is physically oriented toward the person speaking. Whether sitting or standing, the listener faces their body toward the person speaking. Their eye contact is focused on the speaker, instead of on other distractions or priorities. An active listener’s posture is upright and engaged, versus slouched or withdrawn. One way that we teach this most basic active listening skill is by pairing students up and posing a question, such as, “What was the most meaningful moment of your life?” “What do you look for in a friend?” “Describe your favorite vacation and explain what made it great.” Depending on the bond between the students, you may want to ask more low-stakes questions for less-familiar students, who may be hesitant to show vulnerability with a new peer. After you’ve given the pairs some time to think about their response, you then share that the first person will have an entire minute to share their answer, while the second person can only listen and communicate using their body. After a minute, they switch roles. In this minute, the listener can nod, raise their eyebrows, lean forward, clasp their hands, smile…but they cannot speak. It is quite entertaining to watch the listeners, on the one hand, struggle with not being able to chime in with their own experience–but that’s exactly the point. Forcing them to refrain from speaking helps them focus on the behaviors they can employ to show empathy and understanding. On the other hand, more reticent speakers may struggle with filling an entire minute with speech. This struggle brings us to our next strategy.

(2) Embrace silence

Ahh, silence…usually paired with the adjective ‘awkward,’ silence in a conversation is where the magic really happens. Just because someone is not speaking doesn’t mean that they aren’t thinking. Silence is often an indicator of thought processing, metacognition, and introspection. In an activity like the one we just described, there is bound to be silence in the first round or two of practicing active listening. It may be wise for teachers to–after the first round–ask them how they felt about the silence. Did it make them feel anxious? Did it make the speaker feel frozen? Did it make the listener want to fill the gap? What is it about silence that makes us feel awkward? These are questions worth pondering. In the second round of the activity we’ve described, the teacher can direct the students to pay attention to the moments of silence in the conversation. The listener might consider why it is difficult for the speaker to continue elaborating or sharing. What might be holding them back? Fear? Distrust? Lack of experience or opinion? These kinds of considerations are the (literal) unspoken factors in a dialogue that can communicate volumes. Challenge the listeners within the pairs to amplify their nonverbal skills, depending on why they think the speaker is silent. This could be a time to maintain eye contact, offer a knowing glance, or give an encouraging nod.

(3) Summarize or paraphrase the speaker’s statements back to them using key words

Once students have gotten more comfortable with using their nonverbal communication skills, teachers can offer up a new prompt to discuss and a new challenge for the listeners. In this round, the listeners are able to speak. “Yippee!” they will surely scream…but not so fast! The focus is still on the speaker. This time, the only time the listener can speak is to paraphrase the speaker’s statements back to them. Paraphrasing is different than simply repeating what the speaker said, word for word. It involves paying attention to certain words that the speaker touches on in order to discern a theme. Based on the speaker’s language, what did an experience mean to them? How do they feel about a particular topic? What reasoning do they use to justify their actions? The paraphrasing does not have to occur at the end of the sixty-second round–the listener can paraphrase throughout the minute. The teacher may even double the speaker’s talking time in order to allow for more meaningful dialogue. Paraphrasing can be an incredibly powerful tool. It is a way to show that we are paying attention, that we care, that what the speaker is saying is important and we value their experiences and emotions. Each student should get several rounds of practice with this critical skill, which is essential for any job or relationship in the so-called ‘real world.’

(4)提出探测或澄清问题

Students who have had sufficient practice with paraphrasing the speaker’s words back to them can build upon their active listening skills by asking questions meant to clarify or prompt the speaker to elaborate. Truly another form of paraphrasing, asking questions demonstrates that the listener has attempted to process the sensory data they’ve received and are now intent on filling in the gaps. Asking questions is a way to participate in a conversation without dominating. In the next round of active listening practice, the teacher might ask a new question of the speaker, then inform the listeners that they are now allowed to ask questions. Ideally, they will ask open-ended questions meant to elicit more than a simple yes/no answer; that being said, yes/no questions certainly aren’t off limits! It is important that the teacher model this process. Depending on the nature of the prompt, it might be helpful for the instructor to offer sentence stems to the listeners. For example, let’s say the question for this round is, “What role do you play in your family?” Examples of sentence stems to respond to the speaker might include: “What makes you feel that way?” “How do you know?” “What do you like about your role?” “How would you like to change your role?” These questions compel the speaker to think more deeply about their response while conveying that the listener is paying attention and genuinely curious about the response.

(5) Acknowledge (or better yet, synthesize) a previous point before sharing your thoughts

现在是时候将聆听过程更进一步了。在下一轮对话中,它们可以继续进行,否则老师可以将两个二元组结合在一起,形成一组四人一组。越来越多的参与者意味着更多的信息和情感吸收,这对于那些是新手积极聆听的学生来说可能会更具挑战性。无论学生组合如何,下一个积极的聆听级别都会同时成为演讲者和听众。一个警告是,在分享自己的思想之前,每个学生必须先承认上一点点。句子词干在这一轮中绝对有用。诸如“我了解……”和“当您说……”和“我同意”之类的词干是一些有用的例子。通过承认上一位演讲者的观点,新发言人表明,他们不仅在努力分享自己的意见。它表明,在大声疾呼之前,他们考虑了上一个演讲者的信息,并用自己的观点,信念或经验将其综合起来。

(6) Seek first to understand, then to be understood

Readers may recognize this strategy, as it’s one of Stephen Covey’s 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. In fact, Dr. Covey considers this habit to be the most important principle he has learned in interpersonal communication. After practicing in a group of four, the instructor can then combine two groups into a large group of eight. Obviously, a minimum of five minutes is needed for a larger conversation. One strategy we’ve talked about before at TeachThought is the3 Before Me策略,学生必须在向老师寻求帮助之前必须寻求其他三名学生的意见。我们将调整该策略以进行积极的聆听练习,并规定该小组中的任何一个参与者必须等到至少三个不同的人讲话,直到他们做出另一个贡献。在让学生参加更大的小组讨论之前,例如苏格拉底研讨会,这种策略可能特别有用。很多时候,那些以学生为主导的对话刚刚开始的人非常关心在基于讨论的作业中获得良好的成绩,以至于他们只是在不承认上观点的情况下吐出任何准备的陈述。这种行为通常会导致一个令人困惑,脱节的对话,其中几乎没有想法的综合。通过在我的策略之前实施修订后的3,学生面临挑战,要真正听到,吸收和综合其他小组成员在做出自己的陈述之前分享的内容。

(7) Emphasize and refer back to the goal of the conversation

说到杂乱的对话,这是自然的for students to veer off track in a larger group discussion. In these cases, the teacher (who is meant to serve as the facilitator) may feel compelled to pause or interrupt the conversation. Instead, we suggest using visual cues to remind students of the conversation purpose. One way of doing this is for the teacher to point to a verbal reminder displayed on the whiteboard. Ideally, the teacher can challenge the students to monitor themselves. Perhaps they can come up with an unobtrusive hand signal–since they will be facing each other in a student-led dialogue, it makes more sense for the students to remind each other without the teacher diverting attention away from the conversation. Of course, all of this is predicated on the notion that the instructor or group of students establish a purpose of conversation in the first place. The purpose can come in the form of a statement or an essential question, such as: “What can schools do to improve the learning experience for students?” We speak from experience when we say that many students may want to share personal anecdotes regarding teachers they dislike, subjects they despise, or times when they felt a sense of injustice. In these cases, students run the risk of veering off-topic from the purpose of the conversation. It’s not that their experiences aren’t valid or relevant, but perhaps the students aren’t taking their contributions a step further by offering a solution for avoiding the things about school that don’t work for them.

(8) Resist ‘sides’ and insist on both critical thinking and empathy

One way to generate substantial student dialogue is to ask relevant–hough possibly controversial–questions. These could be questions that relate to social, cultural, political, or economic ideas, such as: “How should we interpret the 2nd Amendment of the United States Constitution in the 21st Century?” or “Why are vaccine/mask mandates a good or bad idea?” or “What is considered ‘hate speech’ and to what extent should it be censored or not?” These are popular topics in today’s digital and physical society, and students may be eager to share their beliefs. On the flip side, students may also be more resistant to opposing ideas. That being said, if we are intent on producing actual solutions in the real world, we know that involves compromise and a merging of values. One idea to give students practice in resisting sides is to challenge them to take on the stance that opposes their personal beliefs. Teachers may be met with an onslaught of groans and protests, but they can then emphasize the purpose of the conversation (which, in this case, is to develop empathy and critical thinking skills). Naturally, students may need more time to prepare for these conversations–to research opposing viewpoints, gather data, and seek anecdotal evidence. How does this all help with active listening? By having to research the opposing viewpoint, the students are essentially priming themselves to receive information that counters their own experiences.

(9) Consider diverse perspectives and experiences

考虑到不同的观点不同于抵抗侧面。在抵抗涉及防止一种行为的同时,考虑到欢迎一种行为。抵抗方面涉及保持接近中立性,同时考虑各种观点涉及考虑中立之外的一切。在50 Everyday Formative Assessment Strategies,我们详细活动正在进行的谈话ns, where students receive a piece of paper with a 2-column chart. In the left column are enough spaces for each student in the class; on the right side is an empty box large enough for a person to write 1-3 sentences. The teacher can ask a question or issue a prompt, and the students then have a given amount of time to discuss the question or prompt with a new partner. They summarize their partners’ responses in the right column next to that partner’s name. The challenge is for each student to talk to a brand new person in class before talking to one person twice. This is a great activity for classes where students tend to gravitate toward the same partners. It can also be useful as a means of ‘breaking the ice’ before a potentially intense conversation. Actively listening to (and summarizing) one response at a time can prime the student for what they might hear in a larger group discussion. Because all students have spoken to each other, and hopefully listened with intent, there is less pressure to insist on the validity of one’s own beliefs and more focus on empathy and critical thinking.

(10)保持开放mind

There are many similarities between our last two active listening strategies. Considering diverse perspectives is representative of open-mindedness. What we want to emphasize here is how the body can ‘shut the mind off’ from receiving information that isn’t compatible with our well-established beliefs. With a young, impassioned group of students, it is likely that some may become upset, frustrated, sad, or even afraid in a more controversial conversation. When our sympathetic nervous systems are highly activated (aka, we are ”triggered’), we may go into fight, flight, or freeze mode. This involves a biological reaction in which the body prepares to go on the offensive, shut down, or run away. When we are on high alert, we may not be receptive to listening with empathy. We may not prioritize the importance of critical thinking. Something that was said or communicated nonverbally signals to us that we are in danger or that we are being judged. It may be helpful for the instructor to lead a class in mindful breathing techniques if they know that a conversation has the potential to get intense. InHow Can You Teach Mindfulness To Your Students?我们提供十个技巧,以帮助学生练习耐心,转移和利用自己的想象力来保持神经系统的平衡。在进行大型小组讨论之前,教学学生如何识别自己的神经系统能量在增加以及其他人何时开始工作可能很有用。这并不是说我们一定要防止能够识别和管理它们的能量中的这些尖峰可以帮助我们保持接受。我们不仅正在学习如何积极地倾听他人,而且我们可以积极地倾听自己的身体。